|

View: 31577|Reply: 153

|

[PERBINCANGAN] Belajar Apa Sahaja Berkaitan Jepun

[Copy link]

|

|

|

Post Last Edit by juju_amin84 at 26-3-2012 22:24

Kepada forumer yang dihormati sekalian,

Siapa tau kat mana tempat(kalau ada kat area Melaka ni lagik best)@website@artikel@buku yang membolehkan sya belajar mengenai negara jepun?

Tak kira la dari segi bahasa,budaya,sikap,dan lain-lain yang ada kaitan dengan Jepun

Kalau maklumat yang ada dlm Cari forum pun boleh gak dikongsi dgn sya,dah puas merayau kat Cari nie tapi tak jumpe2

Minta tolong yer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reply #1 the_slayers's post

blh google kan wak...any infos about jepun .....ahakss.....kalo nk buku lagik sng ......kt mph ...sumer ader ...try carik buku lonely planer ...ttg jepun...mmg sng ....sumer infos ttg jepun ader.....nk blaja bhs jepun pn sng ..byk buku ader jual.. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Originally posted by juju_amin84 at 24-2-2008 04:07 PM

blh google kan wak...any infos about jepun .....ahakss.....kalo nk buku lagik sng ......kt mph ...sumer ader ...try carik buku lonely planer ...ttg jepun...mmg sng ....sumer infos ttg jepun ader. ...

ooo...yer ker..tenkiu..

dee mana...

aku dah terpos thread ni bnyak2,

sorry... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Originally posted by juju_amin84 at 24-2-2008 04:07 PM

blh google kan wak...any infos about jepun .....ahakss.....kalo nk buku lagik sng ......kt mph ...sumer ader ...try carik buku lonely planer ...ttg jepun...mmg sng ....sumer infos ttg jepun ader. ...

lonely planer ker lonely planner atau lonely planet?sape pengarang buku tu juju? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Japanese Changes in Work Attitude

Introduction In the years 1960, 1976, and 1990, Shinichi Takezawa conducted worker perception studies at each of two plants in the steel and plate glass industries in Japan. He then used the data to give an overall perspective of human resource management and industrial relations in major private industries in Japan. All the participating production workers were male and randomly drawn from the perspective major operation centres. The two companies chosen for this study were NKK Corporation and Asahi Glass Company, Ltd. Professor Takezawa presented the results of his survey in "Japan Work Ways", a book published by The Japanese Institute of Labour in 1995.

Although fascinating in many respects, the survey is particularly helpful in measuring the historical trends of the attitude of Japanese employees to work. While the survey originally was conducted as a comparative study of work attitudes in the United States and Japan, the scope of this paper will be limited to explaining the reasons for the shift in attitude towards work that has occurred among workers in Japan. To better relate the attitude changes to macroeconomic alterations and other factors, the survey measurements will be aligned with several well-known theories on Japanese human resource management. Before commencing with a comparison of specific numbers, however, it is necessary to summarise the four stages that, according to Takezawa, have occurred in the development of industrial relations and human resource management in Japan from 1945-1990,

The Four Stages The first stage, which Takezawa terms "Labour and Management: Acceptance as Partners", concerns the periods of tumultuous labour-management relations that followed the Second World War and lasted until about 1960. Socialist influences and radical labour unions made extensive demands in terms of wage increases and other benefits, and strikes were rampant. However, there soon developed an understanding that constant labour disputes were detrimental to both management and workers. In the words of Takezawa: "Through such years of trial and error, both managers and workers at each enterprise began to learn how to live and work together with each other". What they discovered was that their interests were interlinked, and perhaps most important was the development of the enterprise union.

As the economy continued to expand rapidly, Takezawa argues that the relationship between management and labour continued to develop during the second phase, which he terms "Growing Investment in Human Resources". The system of lifetime employment began to develop during the period from 1955-1973, as did related characteristics of the HR system such as job training and also what will later in this paper be referred to as the horizontal information structure. In addition, the importance of performance appraisal started to grow, and the traditional line between white-collar and blue-collar workers was slowly removed.

The fourth stage in the development of industrial relations and human resource management commenced with the first oil shock in 1973, as Japan was forced to move into high-value added products. Evidently, the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971 did not help to ease this impact. The headline Takezawa gives the period, namely "Meeting New Challenges", does in this regard hit the spot. This serves only as a brief introduction to some of the major changes that took place in Japan following the Second World War, and should in addition help demystify the Japanese human resource management system. While the latter undoubtedly was very successful and effective during the period of high economic growth, the system is rather recent and has experienced some remarkable changes during the last few decades. As the Japanese economy is in the doldrums, pressure on the system to reform is derived from both domestic and foreign sources. Some commentators argue that Japanese institutions and people are unable to change, mainly due to embedded conservatism and a general resistance to change. Japanese history, however, tells a different story, as do the numbers presented by Takezawa抯 survey.

Absence of Resistance to Change The first of the three surveys presented by Shinichi Takezawa was conducted in 1960, thus after the years of domestic instability following the Second World War. One of the first tables introduced in Takezawa抯 book is in fact not from his own survey, but actually adopted from The Institute of Social Problems in Asia (1982). It comments on the attitudes towards technological advances in West Germany and Japan, and shows that 76.7% of Japanese workers had a positive inclination towards implementing technological innovations in their company, while the corresponding figure for West Germany was only 31.6%. Perhaps part of the explanation for this discrepancy can be derived from cultural issues. However, a more likely explanation is that while many German factory workers would agree with the following Karl Marx quotation, few Japanese workers would: "Capitalist production, therefore, develops technology, and the combining together of various processes into a social whole, only by sapping the original sources of all wealth - the soil and the labourer".

It is likely that Karl Marx would have been surprised to see the unique labour-management relations that have developed in Japan. "The Japanese firm", says Stanford Professor Masahiko Aoki, "should be regarded as a coalition of the body of the employees and the body of stockholders rather than the sole property of stockholders, as postulated in the neo-classical paradigm". In Western countries, the management of a company will generally view new technology as a potential cost cutter, the latter usually in the form of a reduced head count. Workers are thus, perhaps understandably, skeptical to the benefits they will derive from the introduction of new machines or robots. T.J. Pempel, a much quoted expert on Japanese political economy, simply underlines this by saying: "Core workers in Japan rarely faced layoffs; in periods of financial stress their bonuses might be reduced, the oldest workers might be "tapped on the shoulder" and encouraged to take early retirement, or workers may be reassigned to new jobs". This certainly helps explain the positive attitude of Japanese workers to technological change, yet also points a finger to the dire economic problems faced by Japan today. While Japanese companies have been experiencing slumping profits for more than a decade, most have been reluctant to cut the payroll, which again implies that the Japanese human resource management system is undergoing a slow change to economic reality. On the other hand, while the reluctance to fire workers may cause difficulties in times of economic downturns, positive results can be derived in terms of improved company morale.

To further emphasise that the positive Japanese attitude to new technology is a result of a different organisational structure rather than pure cultural differences, a look at Takezawa抯 own survey may prove enlightening. In 1960, 21.5% of the NKK respondents said they would actively resist the introduction of new work-saving machines to their company, while an additional 14.2% would do so quietly. By 1990, however, the figures had been marginalised to 2.4% and 6.8% respectively, thus showing that stakeholder relationship that exists within Japanese companies in fact developed over time. According to Professor Ballon, "the stakeholder system embodies a community of fate, a social context diligently supported by Japanese legal practice and courts". Evidently, job security and the perceived sense of being rewarded as the company progressed contributed to creating the positive attitude toward technology. As is shown from Takezawa抯 survey, any reform to the Japanese human resource management system is bound to have both positive and negative effects, as any breakdown of the coalition that exists between workers and management will lead to lowered worker loyalty and perhaps even internal resistance to corporate reform.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cooperation and Work-Group Morale In 1960, 28.4% of the respondents at NKK Corporation said they desire their co-workers to "work at maximum capacity, without endangering their health, helping others when their own tasks are completed". In 1976 and 1990, this figure had risen to 54.6% and 56.4% respectively. At Asahi Glass, the responses were similar, although less dramatic. This does certainly emphasise that the level of group commitment within the company saw a fundamental change during the period 1960-1990, and also indicates that workers felt they share in the benefits of the company. In the book "The M-Form Society", William G. Ouchi attempts to explain the clan culture that has developed within many Japanese companies, namely that the members of the organisation feel they have an obligation beyond the simple exchange of labour for salary. Evidently, the steel industry in Japan experienced incredible growth until around 1975, and Richard Katz comments in "Japan 丒The System that Soured", that the steel sector was one of the industries that basically drove the Japanese economy forward during the high growth era. The answers given by the workers of the NKK Corporation evidently find much of their origin in the job security this provided, although they certainly had less reason to be optimistic when interviewed for the survey in 1990. Notwithstanding, in the NKK Corporation, the high morale of workers derived from the belief that workers in the long-term will benefit from the gains of the company. "One clan member", comments Ouchi, "may be unfairly underpaid for three years before his true contribution is known, but everyone knows that his contribution will ultimately be recognised". Another set of numbers presented by Professor Takezawa shows further evidence of this.

When asked what is the best way to get satisfaction if one feels that the rate of compensation received is unfair, in 1990 34.4% of NKK抯 employees answered that the best thing to do is to show patience and confidence and management by not voicing a complaint. However, in 1960 and 1976, the figures were only 16.3% and 30.8% respectively. Still, it should be noticed that in all three surveys, more than 50% of the NKK抯 workers and more than 60% of AGC抯 workers responded that the best alternative would be to complain through one抯 supervisor or union representative.

Changing the Incentives Structure

Masahiko Aoki considers there to be two fundamental incentive problems that face all large business organisations, these being the moral hazard problem and the adverse selection problem. He then argues, however, that Japanese firms are faced with two additional incentive questions. First, it is necessary to encourage employees to stay with the firm for the long-term, in order for them to acquire the contextual skills necessary to become a part of the clan culture as described Ouchi. Second, Japanese firms need to promote productive co-operative behaviour in team production. In fact, the above rather rosy picture presented of the inner workings of a Japanese firm does only present half of the story. "The fact is", comments Professor Robert J. Ballon, "that the internal labour market sponsored by larger companies, while providing relative stability of employment, requires unremitting rivalry among contenders for promotion, probably matched in intensity only by the plight of employees in a struggling small company".

Professor Takezawa comments that the move towards performance based pay was particularly strong in the last of the four phases he describes. Due to a growing awareness of the importance of recognising individual differences in promotion and remuneration, workers at both NKK and AGC began to expect to earn more if they worked harder. In the case of ACG, only 12.5% expected an increase in remuneration when asked in 1960, while the figure had grown to 29.1% by 1990. While this may be interpreted as a weakening of the group culture, it may argued that the improved conditions had raised expectations in terms of salaries and other benefits. However, even at AGC, an overwhelming majority answered that they were motivated for other reasons than for instance an expected salary increase. For example, 34.9% of the AGC 1990 respondents replied that they are willing to work hard at their jobs because "they want to live up to the expectations of their family, friends, and society". It would be far from radical to suggest that the corresponding figure in the United States is much lower.

The movement towards evaluating and comparing workers is describe further by numbers presented on how workers believe the satisfaction of employees can be satisfied. At AGC, 28.4% resisted any form of evaluation and comparison of individual performance when asked in 1960, but only 10.7% held this view when asked in 1990. In both AGC and NKK, the overall tendency of a larger acceptance of worker evaluations seemed clear. Robert J. Ballon argues that "the post-war egalitarian approach that Japanese large companies adopted in wage administration is undergoing a significant evolution". Further, he comments that "Another much-talked-about development is stock options for top executives in large companies, with the hope that this would stimulate them to pay greater attention to shareholder value and commit them to financial disclosure more in line with international standards". It remains to be seen what impact this development will have on the earlier described clan culture that exists within Japanese companies, yet some may hope that Japanese companies have lost their fascination with stock options after the recent accounting scandals in the United States. Although Professor Ballon mentions lack of transparency as one of the potential problems faced by the stakeholder system, the American system of corporate governance and Arthur Anderson accounting may not appear to be much more effective.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Decision Making and Promotions When asked how higher management should decide upon promotion to various supervisory levels, only 35.6% of the 1960 NKK respondents would entrust higher management to do so on its own judgement. By 1990, however, this number had climbed to 65.5%. At AGC, however, the figures for 1960 and 1990 appear relatively similar, thus there is different to track any significant change in attitude toward promotion. In contrast to typical American functional hierarchies, Masahiko Aoki uses the term ranking hierarchy to describe Japanese companies. The basic remunerations to employees are associated mainly with their ranks in the system, Aoki considers it misleading to use the term internal labour market to describe the Japanese firms. Some observers view the ranking system as a device for promoting learning and preserving costly skills within the firm, a process which is evidently made impossible if workers do not stay with the firm long-term.

Another interesting part of the survey concerns decision sharing, and how a supervisor should go about when it is necessary to implement changes in work methods. In 1960, 74.6% of the AGC respondents answered that the supervisor should first ask workers for their suggestions regarding proposed changes, while only 54.1% gave this response in 1990. Overall, however, the figures show that the stakeholder principle remained strong in both organisations, and only 4% of the AGC workers responded that the supervisor should decide himself without consulting the workers. According to Ouchi, one of the main strengths of what he terms the M-Form company, which basically means a Japanese firm, is that unnecessary centralisation is made superfluous by localised problem solving. "If teamwork is lacking in the middle management of an M-Form company", he writes, "all the disputes will be passed to the corporate office for resolution". This principle appears valid for all levels of the organisation, and workers therefore expect to be informed and involved in decision making. If, on the other hand, management ignores them, passive and active resistance within the organisation is likely to arise.

The Paternal Organisation While several aspects of the Japanese HR system can be explained through various theories and historical trends, others are more difficult to grasp. Professor Takezawa presented this hypothetical scenario to both NKK抯 and AGC抯 workers: "If you expect that your company will experience a prolonged decline in business, and if you can get a job with a more prosperous company". In 1960, only a few percent responded that they would leave the firm and accept the offer from the more prosperous company. By 1990, this figure had risen to around 18% for both companies, yet the overwhelming majority would still choose to remain with their current employer. This does again point back to the earlier described stakeholder system, and more than implies that workers consider their company to be more than merely an employer. Although this has altered somewhat over the last few decades, the change has been far from dramatic.

Very related to this are numbers presented to describe how Japanese workers think of their company. In 1990, 63.2% of respondents at NKK and 48.4% at AGC considered the company to be "a part of my life at least equal in importance to my personal life", while an additional 4-5% though of the company as being even more important than their personal lives. These figures, while having decreased slightly, show little change from 1960. Evidently, this brings Confucian and cultural values such as filial duties into question, yet these are harder to decipher than human resource management theories and socio-political economics. Some weaknesses of the system, however, can be described using very basic economics.

Conclusion: Working it Out In the same way as a sweet and stable relationship developed between workers and management, industry and government developed similar ties. Professor Katz argues that there are several weaknesses to this system: "Once established, however, the relationship between industry and government becomes difficult to terminate; thus industrial policy continues, becoming nothing more than protectionism, and maybe even hampering the development of a competitive environment in the economy as a whole". The same can be argued about the Japanese stakeholder system, as the latter may make it more difficult to implement quick changes during times of economic difficulty.

Still, Japanese workers appear to have become relatively reconciled with the possibility of facing layoffs during economic downturns. While 38.2% of NKK抯 workers in 1960 would expect to be urged to resign if a company抯 business should decline by fifty percent, the number had by 1990 risen to 60.3%. Still, it should be emphasised that they also would expect to receive special severance pay in addition to any accumulated retirement benefits. These expectations have made it excruciatingly expensive to restructure Japanese companies, but perhaps the breakdown of the stakeholder system is an even higher price to pay.

While Takezawa抯 survey points to several important changes in attitude that occurred between 1960-1990, Japan currently finds itself in an economic reality very different from that of any of the years in which the survey was conducted. According to Richard Katz, Japan抯 problem during the last decade has been "continuing the same patterns after the catch-up era was over". Japanese workers got well adjusted to a stable relationship during the high growth years that continued almost relentlessly until the burst of the bubble. Now, as the high growth years are far gone, Japanese management-labour relations will slowly have to adjust to this new reality.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Persiapan utk bekerja di kilang Jepun

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Japanese Culture -- A Primer For Newcomers

This site is to familiarize you witha few basic characteristics of Japanese culture and behavior that the westerner will encounter.There are many reactions and attitudes that Japanese will give off -- many of them the typical westerner would ordinarily not pick up on. But if you come to Japan and want to have better relations, as well as a better understanding of how many Japanese people think and perceive you, there are a lot of key items you should be aware of. Some you may like and others you may not. That, of course, is fine -- you're entitled to your own views, no matter what anybodyelse says. But you will have to deal with some of the cultural and behavioral aspects whether you like it or not. Those that can recognize and deal with the differences in Japaneseattitudes will adapt faster, get better jobs, and have a more positive experience living inJapan. Do not feel that you will ever have to completely understand the Japanese, since the Japanese don't completely understand themselves either.*Important*: Japan has a lot of positive traits, and a lot of negative ones also. You'll find Japan captivating, bewildering,enchanting, enraging, humorous, frustrating, loose, uptight, accomodating,and anal-retentive -- sometimes all at the same time. However, the contentsof this site center more on the negative aspects than the positive ones since these are what make life for westerners more difficult here. They aremeant to show more of what culture shock is experienced and are *NOT* to be taken as an accounting of the number of good traits vs. the bad.

Here are a few basic traits to remember--- Uchi-Soto -- Us and Them

- The Gaijin Complex

- Honne and Tatemae -- The Real Mind & The Veneer

- Osekkai! -- Mind Your Own Business!

- "Goatism" -- Giseisha and Urami -- On Scapegoats, Victims, and Envy

- Amae -- Dependency

- Tate-shakai -- The Vertical Society

- Shikata ga Nai and Gaman -- You Can't Fight City Hall

- Nihonjinron and Kokusaika -- We Japanese & Internationalization

- The Iron Triangle and the Empty Center

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JAPANESE MANNERS AND ETIQUETTE

Here's a word about good manners while living in Japan. Up to now, unless you've been living in a cave, you must have heard about taking off your shoes before entering a residence and not getting into a bath while still soapy, since others have already talked these issues to death. But there are a lot more items you may not know. Japanese are very conscious about hygiene (except for the park and train station toilets, which are LETHAL), and Japanese are a very sensitive people -- more fastidious about etiquette and proper form. Many Japanese already have a negative image of westerners after observing how some have acted in Japan--hence the reputation of some landlords and real-estate agents not to rent their apartments. Whether you help dispel their preconceptions, or just reinforce them by acting like you belong in a zoo is entirely up to you.

Whether you are in Japan for tourism, travel, or living in Japan, your actions have a profound impact on how others perceive you, particularly important if you're lookingfor work. As anywhere, many social customs are done away with when in the company of family and closefriends, but for coworkers and more formal situtations, it can help a lot to remember these.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eating- It is impolite to eat or drink something while walking down the street.

- Do not bite or clean your fingernails, gnaw on pencils, or lick your fingers in front of others.

- In restaurants or when visiting it's customary to get a small, moist rolled-up towel (cold in summer, hot in winter) called an "oshibori" to wipe their hands with. It's impolite to wipe the face and neck with it though some do in less formal places.

- In Japan it is impolite to pour your own drink when eating with others--you pour your companion's drink and your companion pours yours.

- If you don't want any more to drink, leave your glass full.

- It's customary to say "Itadakimasu" before eating and "Gochisosama de#a" after eating, especially if you're being treated, as well as "Kanpai" for "Cheers".

- When sharing a dish, put what you take on your own plate before eating it.

- Do not make excessive special requests in the preparation of your

food, nor wolf it down. - Do not use your chopsticks to skewer food, move dishes around, and

NEVER dish out food to another using the same ends you just ate

from--use the top ends. - Don't use your chopsticks to point at somebody.

- Don't leave your chopsticks standing up out of your food.

- It is normal in Japan to pick up your rice or miso soup bowl and hold it under your chin to keep stuff from falling.

- Traditional Japanese food is served on several small plates, and it's normal to alternate between dishes instead of fully eating one dish after another.

- Don't leave a mess on your plate--fold your napkins neatly.

- Don't take wads of napkins, sugar packs, or steal "souvinirs" when you leave a restaurant.

- Do not put soy sauce on your rice--it isn't meant for that.

- Do not put sugar or cream in Japanese tea.

- There is no real custom like "help yourself". Wait until the host offers something.

- If you act as host, you should anticipate your guest's needs (cream/sugar, napkins, etc.).

- If you must use a toothpick, at least cover your mouth with your other hand.

- Be aware that in Japan it is normal to make slurping sounds when you're eating noodles.

- In Japan, it's good (in commercials, anyway) to make loud gulping noises when drinking. Expect to hear lots of it in ads.

- It is normal to pay a restaurant or bar bill at the register instead of giving money to the waiter/waitress. There is no tipping in Japan.

- It's considered rude to count your change after paying the bill in a store or restaurant, but the Japanese themselves do give it a cursory lookover.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Everyday Living- Thou shalt NOT BE LATE for appointments.

- There is no custom of "Ladies First".

- Avoid excessive physical and eye contact--forget the back-slapping,

prodding, and pointing directly at someone with your finger (use

your hand to point, if you must). - Japanese often use silence for communication as much as speaking.

- Do not chew gum when working or in other formal situations.

- When Japanese start work at 9 AM, they START WORK at 9 AM.

- Avoid lots of jewelry or very colorful clothes when going to work.

- White-collar Japanese typically leave the office only after their superiors have done so. Do not expect someone to be instantly free once the official business hours are over.

- Exchanging business cards is de rigueur in formal introductions. You should extend your card to the other person with both hands, right side up to them (upside down to you). You receive cards with both hands also. Be sure to look at the card and not just pocket it. Never put it in your pants pocket and sit on it in front of them.

- It is polite to put "-san" after anothers name, or "-chan" after a young girls name,or "-kun" after a boy's name, but NEVER use these after your own.

- Do not scream about why nobody speaks English, why there aren't

5 different varieties of a product you want, or why workplaces or

restaurants are filled with chain-smokers. The "health thing" is

not big here yet. - Avoid shouting loudly at someone to get their attention--wave, or go up to them.

- If you have to blow your nose, leave the room, or at the very least try to face away

from other people--and use a tissue--not a handkerchief! - Don't wear tattered clothes outside, nor socks with holes when visiting someone.

- On escalators, stay on the left side if you plan to just stand and not climb them.

- Japan has no tradition of making sarcastic remarks to make a point,

nor "Bronx cheers" or "the Finger" -- avoid using them. - The Japanese gesture of "Who, me?" is pointing at their nose, not their chest.

- The Japanese gesture for "Come here" is to put your hand palm out, fingers up, and raise and lower your fingers a few times. The western gesture of palm-up, closing your hand is only used to call animals to you.

- The Japanese gesture for no is fanning your hand sideways a few times in front of your face.

- Japanese residences have thin walls and poor insulation - don't blast your stereo or television.

- Don't wear your slippers into a tatami (straw) mat room.

- It's customary to sit on the floor in a tatami room (called "wa#su").

- Don't wear your slippers into the genkan (at the entrance to a home, where the shoes are kept), nor outside.

- Don't wear the toilet room slippers outside the toilet room.

- It's better to wear shoes slipped on easily when visiting someone.

- Japanese wear kimono or yukata (light summer kimono) with the left side over the right. The reverse is only for thedead at funerals.

- It's polite to initially refuse someone's offer of help. Japanese may also initially refuse your offer even if they really want it. Traditionally an offer is made 3 times. It may be better to state you'll carry their bag, call a taxi, etc., instead of pushing them to be polite and refuse.

- When they laugh Japanese women often cover their mouths with their hand. This comes from an old Buddhist notion that showing bone is unclean, as well as a horrendous lack of orthodontics in Japan.If you're a woman you have no obligation to copy this, but you will soon notice how frequently Japanese do this.

- It's polite to bring some food (gift-wrapped in more formal situations) or drinks when you visit someone.

- Gift giving is very important in Japan, but extravagant gifts require an equal or slightly higher extravagant gift in return. Avoid giving pricey gifts.

- Giving cash is normal for ceremonies like weddings and funerals; but given in special envelopes with a printed or real red tie around it (available in stationary and convenience stores). Use new and not old bills.

- After coming back from a vacation it is normal to bring a small gift for all those you work with, even if you don't really like them a lot. Nothing expensive is required, however.

- It's polite to belittle the value of your gift or food when you offer it, even if it's blatantly untrue.

- In more formal circumstances it's impolite to unwrap a gift someone brings you as soon as you receive it. In casual surroundings it's normal to ask the giver if it can be opened now.

- It's polite to see a guest to the door (or the front of a building even) when they leave.

- When someone visits it's polite to turn their shoes around and put them together so they can put them on easily.

- This is older custom, but in a home the guest is seated facing the room entrance. The highest ranking host sits across from the guest.

- Again old, but in a car the highest ranking person sits behind the driver. The lowest rides shotgun.

- For taxis the driver will open/close the rear left hand door for you.

- Japanese often compliment eachother to promote good will, but it is polite to deny how well you speak Japanese, how nice you look, etc.

- In Japan the whole family uses the same bath water -- as a guest you will probably be given the priviledge of using the bath water first. Do NOT drain the water out after you have finished your bath!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Japanese New YearWhat would you think is the most celebrated holiday in Japan? The Emperor'sBirthday? The nation's foundation day? Groundhog Day?!? Nope -- it's Jan.1st -- New Year's Day. And during the first few days of the newyear you'll find EVERY SINGLE SHOP shut down tight. With Japan's economyheading straight down into thetarmac though, these days you see a few shops opening earlier trying to pullin more warm bodies. Are theysuccedding? Partly, yes. While in North America people spend Christams withtheir families and whoop itup New Year's, in Japan it's (just like for nearly everything else) exactlythe opposite. TV is dull, dull, dull. Shops are closed. Videos rental shelves (for those that are open) are raped and empty. Streets are deserted.Until recently up to 10% of the whole population of Japan would celebrate the JapaneseNew Year by running like hell to the airport and getting out of the country. Millionsstill do though, since Japanese are given extremely few chances to go abroad in the year, theJapanese festivals are quiet and dull, and escaping the bitter cold of the season is a niceidea. For those that don't leave though, here are a few pics of what they do....

Osechi Ryouri -- New Year's Cooking

There are many kinds of Osechi for New Year's. Many are wildly expensive also -- as you can see in oneone the pictures -- 2000 yen for a small case of sweet black beans. Other dishes you can see look likegoldfish on a stick, but aren't. There are small shrimp strung together, various baked fish, sweet jams,fried foods, etc. In older times women slaved for several days to get everything done, but these daysthey just go to the supermarket and pay in blood.

The New Years DisplayMany large stores also have large ornaments like these seen here. Three bamboo poles decoratedwith flowers and pines are very typical -- but different regions of Japan have slighty differenttypes of New Year's displays.

And here are some pics of a shrine on New Year's Day --

The Shinto Shrine is the only busy place you'll find on New Year's. Many people on the night ofDec. 31st go to a Buddhist temple to hear the 108 bongs of the bell, which are supposed to drive offthe 108 sins of the human condition. Traditionally, many visit 3 different shrines on New Year's, anda few actually stay up all night to do it and see the first sunrise of the year. It's about the only timethat public transportation is running in the wee hours of the morning; normally they shut down beforemidnight. Some of the more famous shrines will be jammed with people, as they go up to thealtar and pray for health and prosperity for the coming year. It is also one of the few timesthat you can see some Japanese women in a traditional kimono. Japanese also receive Nenga-jo orNew Year's Cards, and that is the only mail delivered on Jan. 1st. Some mail out several hundredcards to every acquaintance and business contact they have, much to the delight of the Post Officewhich makes godzillions of yen from it.

Fireworks are generally NOT used, but this too due to the whoop-it-up atmosphere of the Westis slowly changing, and in some more populated areas or amusement parks you can see some. You won't find anyhome fireworks on sale anywhere though, and if you want to light some up you had better buy them when they are on sale, during the summer usually til the end of August. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Seijin No Hi -- Coming of Age Day (January 8th)

Seijin No Hi is the first holiday of the year after New Year's is all over. It is for all the womenwho have just become legal adults (age 20), and most families buy a kimono for theirdaughter. The typical kimono is 300-400 thousand yen, but much more extravagant kimono can be even ashigh as a million yen each. On the day the young lady will typically go to a nearby Shinto Shrineand pray for health, success, money, etc. It's one of the few times you will see anyone wear a kimono -- except for the grannies running around going to study or teach tea ceremony. The other occasions aregraduation from a college, and once in a while at a wedding. And if you're one of those country oakies thateats roadkill for dinner and still thinks Japanese dress like this every day, WAKE UP!!

Valentine's Day

There's Valentine's Day here in Japan too. But not quite thesame. In Japan, it's the GIRLS who give the boys chocolate on Feb.14th. And not just to someone they like. There is a uniquely Japanesecharacteristic of giving "Giri-Choko" -- giving chocolate to the menone would rather see skydiving without a parachute -- the boss, namely."Giri" means obligation, but in Japan it has a deep sense of long-termcommittment.

Since gift-giving is a common custom in Japan, many confectionary companies also try to pushtheir own manufactured celebration, "White Day" on March 14th, where it's the boys turn to give thegirls something. This attempt has been at best a limited success.

The Hina Matsuri

The Hina Matsuri or doll festival takes place on March 3rd every year. Its origins go back to China which had thecustom of making a doll for the transferral of bad luck and impurities from the person, and then putting the doll ina river and forever ridding oneself of them. March 3rd celebrates Girls' Day in Japan, and from mid to late Februaryfamilies with daughters put out the dolls with the hopes their daughters will grow up healthy and happy.One superstition associated with this is that if they are late in putting away the dolls when the festival is over, theirdaughters will become old maids. Most displays consist of just a prince, (Odairi-sama) and a princess (Ohina-sama), butmore elaborate displays include the dolls being part of a 5 or 7 tier diplay (hinadan), along with courtiers, candy, rice boiled with red beans (osekihan), white sake (shirozake), peach blossoms,diamond shaped rice cake (hishimochi), toys, and tiny furniture. Traditionally many parents or grandparents will begin their firstdisplay for their daughter, called hatsu zekku,when she is just a year old, but some families have passed theirdolls down from generation to generation with the bride carrying herdolls with her to her new home. Aside from the displays, Japanese usedto go view the peach blossoms coming out, drink sake with a blossom init, and bathe in water with the blossoms.The blossoms represent desirable feminine qualities, includingserenity, gentility, and equanimity.

The festival evolved into the form wecan see today during the Edo Period (1603-1867), and it is still possible for people to buy Hina Matsuri dolls createdduring that time as well as the late 19th and early 20th centuries in antique shops during the season. Two areas that comealive with such displays and events like those above is Yoshimura and Yanagawa, both in Fukuoka Prefecture.

Cherry Blossoms

The coming of the cherry blossoms (sakura) is one of the happiest events in Japan. First and foremost it heralds the coming of spring, which is a delight since winters in Japan are bone-chilling cold. They also have a deeper cultural significance since they fall to the ground and disappear in only a couple of weeks (and even sooner if the frequent rainswash them all off the trees), which echoes an ancient cultural belief in the short, transitory nature of youth and life itself. These photos showthe flowers and how Japanese celebrate -- the Hanami, or flower viewing. What this means of course is another bout of wild drinking parties under the trees, and karaoke going until the wee hours of the morning. Every city park with lots of sakura trees will be jammed with people, and finding a spot to even sit down may be impossible. The last photo as you can see is another example of Japanese "living in mystic harmony with nature" (be sure to pass this page's URL to all your goofy friends who view Japan with sakura-colored glasses). The aftermath of all this is morethan just a pretty carpet of sakura petals on the ground. Nevertheless, the sakura are truly a delight to behold,it means the end (or nearly the end, as mother-nature sometimes jumps the gun) to those horrendously freezing winter winds, and you haven't seen Japan until you've seen the beginning of spring.

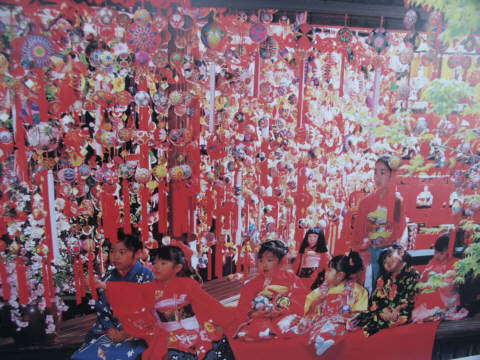

The Shichi Go San Matsuri

The Shichi Go San or 7-5-3 Festival is one of the uniquely Japanese festivals. Boys who are 3 and5 years old, and girls who are 3 and 7 are taken to a shinto shrine, often in their first kimono, and theparents pray for their continuing good health and prosperity. The numbers, especially 3 and 7, arelucky numbers in Japan, and until the 20th century Japan was a thoroughly feudal nation with ahigher childhood mortality rate. Since bacterial pathology was then unknown to them they often blameddeath on evil spirits, and when the kids became 3, 5, and 7 years old they thanked the gods fortheir children's good health. A sweet candy called chitose-ame is also often bought for them, in a bagwith cranes and turtles, 2 more symbols of long life. Other gifts are also given to them, asyou can see some samples like the Japanese animation cat Doraemon.

You might think in a country that's 99% non-Christian that Christmas would just blow onby and you'd never even realize it. But once again, you'd be completely wrong. Japanesedepartment stores have decked-out trees as colourful as anything in the west, and many streetshave colourful displays and wreathes all lined up for blocks. Still, it's time to set the record straight -- it's most certainly NOT as some dewey-eyed western writers put it "one day out of the year whenall Japanese become Christians". Christmas in Japan has nothing to do with religion at all. Thenwhy is it popular? For one, exchanging gifts is a well recognized cultural trait and Xmas fitsin nicely here. For another, the lights and glitter are pretty. But behind that you'll find verylittle else. In fact, when it comes to celebration, think Valentine's Day. Christmas in Japan is morethan anything a time to take an important date out to dinner, and for some even to book anexpensive hotel room for the night.

Do you keep passing along to one of your "friends" those fossilized 15 year-old cakes in the mail every year? Well, they eat those "Christmas Cakes" in Japan. But there is nobig Xmas feast. Turkey is nowhere to be found, unless you want to pay a fortune to a mail-ordercompany or one of the few department stores that carry them. Not much you could do even if youdid have one, since for nearly all Japanese the only oven they have is a microwave or a toaster.So given a choice of a turkey sandwich at Subway's in Tokyo or Osaka, many Japanese go toKentucky Fried Chicken, where there are always some special Christmas chicken dishes. Expect tosee a very long line into every KFC on Christmas Eve. Almost no Japanese have any Christmas treeseither; their homes being cramped enough as it is.

December 25th is still a work day in Japan. There are quite a few parties though. Tis the season for the "Bo-nenkai", or "Forget the Year Party", where many Japanese drink and forget the year's problems (and more than a few drink enough to forget more than that). There is also writing Nenga-jo or New Year's Cards for Jan. 1st. And a few give chocolates or small gifts to boyfriends and such, however hark the herald angels sing won't be something you'll be feeling here. But if you like drinking a few glasses of Christmas cheer, Japan iscertainly the place to be. The beer companies are extremely thankful for Christmas. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Why are Prices in Japan So Damn High??

If you haven't seen the news lately, Tokyo and Osaka have just been declared the most expensive cities on the planet (again). What makes Japan so expensive? Why? And does ithave to be that way? What can the foreign resident in Japan do to avoid getting fleeced?There is no simple, single reason. Nor, for the "MTV Generation", who is raised and programmedto expect instant sound-bytes and have the attention span of a gnat, is there a bumper-sticker,easy quick fix. Some of the issues can and should be dealt with, others are more cultural andwon't be going away soon, if ever. It is not that Japanese are all conniving snakes hellbent oneconomic world conquest, nor that western companies "just don't try hard enough", nor it isas some naive observers say "it's all just the exchange rates". All these elements have some truth in them but don't explain the reasons why. Read on to find a few of the causes--

Contents--- Land Prices, Rents, and Taxes

- Cartels and Collusion

- The Rigged, Bulky Distribution System

- Snob Appeal

- Non-Tariff Barriers

- Consumer Apathy/Ignorance

1. Land Prices, Rents, and TaxesAsk any Japanese why homes cost so much and you'll get the Standard Party Line: "Yes, Japanis a small country with very little land, blah, blah, blah." This of course is true. At 127 million people Japan has almost half the U.S. population in a land space that's a bit smaller than California. But that does not explainwhy a QUARTER of the Japanese population lives in or around Tokyo, or why the ShimanePrefectural government gave away land for free if you agreed to live there at least6 mos. a year. The real reasons are found a bit deeper. In fact, most Japanese themselves, beingcompletely apolitcal, are clueless on how their government or System functions. One of thebiggest reasons why Tokyo is insanely expensive is because the government is based there. AndBig Business is in bed with the politicians and bureaucrats. So if Big Business is based there,that's where all the best jobs are and where everyone wants to live. But there's more. Japanis one of the few nations in the industrialized world that has extremely light property taxes,but if you sell a home the tax is a killer 50%!!. This chokes off the supply of land and for the average Japanese worker owning a home will only be a dream. Some companies in fact have issuedloans to buy a home where your children and then grandchildren, as of yet unborn, will finish payingoff the mortgage. Land is also veryexpensive because floor space per square meter of land is artificially restricted by governmentregulations. Inheiritance taxes in Japan are even more devastating, so dying is a terrible thing to do to your family. Things gotstill worse in the "Bubble Era" of the late 80s to early '90s, which was a rampant speculative boom. Sincethen land prices and rents have fallen dramatically but the real causes have not been dealt withso the problem will not go away. 1. Land Prices, Rents, and TaxesAsk any Japanese why homes cost so much and you'll get the Standard Party Line: "Yes, Japanis a small country with very little land, blah, blah, blah." This of course is true. At 127 million people Japan has almost half the U.S. population in a land space that's a bit smaller than California. But that does not explainwhy a QUARTER of the Japanese population lives in or around Tokyo, or why the ShimanePrefectural government gave away land for free if you agreed to live there at least6 mos. a year. The real reasons are found a bit deeper. In fact, most Japanese themselves, beingcompletely apolitcal, are clueless on how their government or System functions. One of thebiggest reasons why Tokyo is insanely expensive is because the government is based there. AndBig Business is in bed with the politicians and bureaucrats. So if Big Business is based there,that's where all the best jobs are and where everyone wants to live. But there's more. Japanis one of the few nations in the industrialized world that has extremely light property taxes,but if you sell a home the tax is a killer 50%!!. This chokes off the supply of land and for the average Japanese worker owning a home will only be a dream. Some companies in fact have issuedloans to buy a home where your children and then grandchildren, as of yet unborn, will finish payingoff the mortgage. Land is also veryexpensive because floor space per square meter of land is artificially restricted by governmentregulations. Inheiritance taxes in Japan are even more devastating, so dying is a terrible thing to do to your family. Things gotstill worse in the "Bubble Era" of the late 80s to early '90s, which was a rampant speculative boom. Sincethen land prices and rents have fallen dramatically but the real causes have not been dealt withso the problem will not go away.

Still worse, the ever-meddling Japanese government has done it's part to stick its fingers inand make things harder. The Ministry of Agriculture, Forest and Fisheries still pushes a systemwhere there are "farmers" growing food in Tokyo-to, just to say that there are farmers in thearea to have a role in policy making. So just 20 minutes by train out of Setagaya you'll find farmers growing cabbages onland worth billions of dollars. Why? Low taxes--that's why. But the situation is muchthe same in every Japanese city -- the rural areas continue to depopulate, and the cities aregetting more concentrated. North of Tokyo are literally thousands of square miles of landwith almost no people -- but the shots are called from Tokyo, so that's where the VIPs all are. There is one more piece of the puzzle -- other high taxes. Income taxes are not too vicious(to the benefit of the wealthy, of course) but high corporate taxes, sin taxes, subsidies, and a 5% ConsumptionTax all take their toll. Japanese taxes on alcohol and tobacco are high (over half the price is taxes), and imported drinksare often cheaper than domestic ones (except for snob goods, which we'll get to in a bit).The government also has heavy subsidies for Japanese agriculture, especially rice. The governmentgives huge yearly subsidies to farmers, then buys all the rice made at very high prices, and sells it at a cheaper price to avoid the wrath ofthe consumers. So where does the government get its money, everyone?? At the same timeit blocks foreign rice imports (gradually the system will be moved to tariffication, but ifforeign rice is made more expensive than Japanese rice, of course no one will buy it. Latelymore and more farmers are selling outside this system, and itwill be phased out, finally, by 2008). NowJapanese rice costs about seven times the world price. So even if you choose not to eat rice(the Japanese staple food), you pay for it in your taxes anyway. Gasoline is also highly taxed.Currently 54 yen of every liter's (that's 205 yen per gallon) price is tax. And of course there'sthe ubiquitous 5% Consumption Tax, soon to go up in a Japan near you. But Japan's tax is appliedalso to gasoline and alcohol, so you're also paying tax on a tax. It also applies to food, as well as to all parts in the production process: compounding itselfmore and more on durable goods. This alone raises prices on a lot of things, but we've justgotten started.

S |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. Cartels and CollusionThis is also a big factor in making prices soar through the roof. Of course Japan has lots oflaws like The Anti-Monopoly Law and The Fair Trade Commision that are supposed to stopillegal practices, but the FTC has always been understaffed, underfunded, and more of a papertiger than anything else -- just the way Big Business wants it to be. And to be blunt, The Anti-Monopoly Law has hurt consumers as well, by allowing high-priced boutiques and mom-and-popsto block the establishment of big stores (which handle more foreign goods) as well as discountstores which increase competition. Currently the US is pushing for abolishment of the wholelaw. This may bring other troubles though. Japanese social security is woefully inadequate,which is the real reason why all Japanese squirrel away all their money and have the highestsavings rate in the world. But that alone isn't enough. So how will older couples make ends meetafter retirement? The mom-and-pop store, of course. With growing numbers of elderly, thisproblem will reach a crisis in a few decades.

The reason why cartels and collusion are the de facto rule of the land is in the way that theJapanese market functions. And unless foreign firms learn this they are doomed to fail inJapan. In most markets in the world the goal of the firm is profit. In Japan, it's market share.Whenever there is a new product like a walkman introduced, every company cranks out as muchof the product as they can, at razor thin profit margins (sometimes at a loss, even). Then thereis a major shakeout -- usually the firms that have less financial backing (i.e. they don't belongto a keiretsu with a big bank to back them up) have to drop out. In the end, you have a smallnumber of firms, which quickly form a cartel and jack up the prices to make money. Distributionchannels are securely locked away, blocking any would-be competitors. At that point, thegame is over. Japanese business also has cozy ties with Japanese bureaucrats, and often employsthem after they retire in a system called amakudari, which gives them a key player withall the government connections still in place.In the 20th Century, most governments would take up anti-trust legislation; Japanhas actually encouraged the growth of big firms to raise its GDP. Ever since Japanreopened itself to the world in 1868, it has been on an export craze to make money -- while carefully protecting its own industries. Few Japanese even know, let alone know why, aJapanese camera costs more in Japan than in New York. A lot of the reason is that Japan isout to capture market share, while already securing it from competition at home. This kindof strategy, by the way, is why the Japanese market is the most competitive in the world, andif your company is more interested in next quarter's profits you will not survive.

One of the more well known and blatant forms of collusion is called "dango", which is bidrigging, usually by the massive multi-billion dollar construction firms. (Currently 10% ofJapan's workers are in the construction industry). The firms divvy upthe list of upcoming public projects, then each company bids higher than than the agreed uponto get the contract. The firms get a guaranteed contract at a high rate, and the taxpayer getsscrewed. The projects can run into the billions of dollars, such as the construction of roads orKansai Int'l Airport. Some action has been taken against the firms of late but since it can takeover 10 years to prosecute and the fines are relatively minor, there is little incentive to befair. Plus with Japan's economy in a coma throughout the 90s, instead of fixing the real problemsthe politicians are trying to stimulate growth by throwing out more band-aids of pork barrel projects, such as building damsthe local people don't want or the infamous "roads to nowhere". All this when there is now the worst unemployment since WWII, massive public debt and a banking sector staggering under bad loans, andthe Japanese government is officially in debt at 130% of its GDP (the actual unofficial amount could be as high as 270%).Another case is the beverage and beer industry. When Coca-cola announced it would raiseits price to 110 yen per can, every other beverage maker did the same thing. Such is a commonpractice, but there was no extreme need. No explanation was given, and even worse, none waseven asked for. The beer industry is another example. For some reason, all 4 Japanesebeer giants charge exactly the same price. The reason given? All four just happened to choosethe same price at random. Of course. Nearly every industry acts this way. Domesticflights are more than double that in other countries. Companies often keep tightrelationships with distributors and retailers, including advancing them capital theycan't pay back as well as training in selling. And the last thing a retailer isgoing to do is bite the hand that feeds him by selling a lot of foreign goodsthat are far cheaper. This economic policy was designed to strengthen large companies andhave Japan catch up to the west after WWII. Now that Japan has caught up, however, newpolicies have never been implemented, and Japan is stuck with a "dual economy". An excellentanalysis of what has gone wrong was written by Richard Katz. Even the media makes an information cartelof sorts, with it's press clubs (kisha) that all act together and keep other reporters that might report more than the official party line out. The Japanese people all get their news from a self censoring, government mouthpiece press. There is next to no mainstream investigative reporting, or whistle-blowing, deep muckraking stories of the under-the-table deals. Only whena major financial scandal erupts does it ever come out, and after a few weeks of perfunctoryapologies and superficial changes, it's back to business as usual. This doesn't mean there is someshortage of intellectuals in Japan; the Nihon Keizai Newspaper, and magazines like Seiron, Ronza, and Gendai all offer good reporting. But it is impossible to see the inner workings of government andjust how far the corruption goes. Pinning down the responsible party in nearly impossible.

3. The Bulky, Rigged Distribution System(Or: Do you really need 3 people to wrap your hamburger?)For a business to succeed in Japan, it needs at least 2 essential things. One of course iscapital. The other, however, is control of the distribution channels, and this is where manyforeign firms fall short. Japan's distribution system is a complex maze and their are thousandsof regulations to follow. This system is currently strangling the domestic economy.After WWII, Japan had millions of people who needed work fast. So asystem was made that employed lots of workers, though many of the jobs were (and still are) redundant. Also there are often several wholesalers sitting between the producer and retailer, eachtaking their cut. This is one of the principal reasons why just sending the value of the dollarthrough the floorboards didn't work. From Sept. '85 the value of the dollar vs. the yen fell bymore than half. Yet products in Japan made from imported parts/ingredients didn't budge. Thereal reason was that the middlemen were eating up nearly all the savings. When the dollar hit100 yen, the Japanese booksellers still used the old 175 yen/dollar rate, and didn't pass anysavings on to the consumers. (You'd be wise to buy whatever books you want in Japan beforeyou come, since the very same books in Japan will cost 2 or 3 times more). In 2000 Merill Lyncheconomist Jesper Koll noted that Japan has 392,000 wholesalers -- a staggering number.Yet two-thirds of them just sold things to eachother and not retailers or producers, and four-fifths of Japanese wholesalers have less than 10 employees each. Distribution channelsin Japan are extremely exclusive -- usually an arrangement to carry your goods also means only your goods and no competitors. Then they have to fight it out with eachother for the store owners to carry their products on the best shelves; space being extremely limited.For decades Japanese people were told (and they accepted) the notion that higher prices werenecessary to keep the whole nation employed--and Japan has had the lowest unemploymentrates in the industrialized world. Also with land prices so high storage costs are also wildlyexpensive, and with Japan's narrow, poky streets large and cheaper distribution is impossible.Docking fees for ships and planes is also insanely high, and it can cost more to ship somethingacross Tokyo than to ship it across the world. High gasoline taxes and expensive electricity also make transport more expensive. In many ways Japan's distribution system makes up the largest Non-Tariff Barrier (NTB). Other NTBs will be mentioned later.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Snob AppealAfter jumping in head-first into Japanese life, and satiating yourself trying all the typicalJapanese delicacies and drinks, the ex-pat here sooner or later starts to yearn for a little tastefrom home. Yet if you go to the specialty store you'll immediately find that those foods yougrew up with, chili, wine, salsa, tacos, soups, cheeses, etc., are all 2-5 times what you paidback home. And if you want to find some perfume, make-up, or Beverly Hills type of gift, thedifference is even worse. This is one cultural factor not mentioned in many books. For decadesJapan has kept out or highly taxed foreign products for so long that today ANY good that sellsfrom the West immediately has a halo of luxury around it. And for snob-goods, the higher theprice, the higher the demand for it. So don't be surprised to hear about $30 lipsticks or$300 Nike Air-Maxes. Frozen flour tortillas can go for 800 yen a dozen, more than 5 times the price in the US. Concert tickets can cost $100 or more. Sports equipment also commands a high price. And when Johnny Walker Whiskey tried to raise demand by cutting prices on it's JWBlack, demand went DOWN, not up. Even a $5 memo pad from the US is going for $21 in Japan.

5. Non-Tariff BarriersUp to the '70s, there were literally thousands of regulations holding back imports. Nowthere are just hundreds. Today even Japanese Big Business is learning that in order to competeit needs less governmental entanglements. Japanese telephone cartels are suddenly getting competition from call-back companies based abroad, which used to charge 80% less than theJapanese. Today, nearly all the formal tariff and quota barriers are gone. Some apologists declareJapan to be just as free as everywhere else. Yet, market penetration for many foriegn goods isstill insignificant. The reason? The NTBs. Some laws make up some, such asthe prohibition of discount prices on books or CDs, thus blocking any healthy competitionor net commerce like Amazon.com.The rigged distribution keiretsu also forms one, complicated licensing procedures are another, as well as other barriers that also include the languageand cultural differences. Some of these things the West simply can't pressure Tokyo forabolishment. If you want to buy something, you can use any language that youwant. But if you want to sell something, you MUST speak the langauge of yourcustomer. And even if English is the de facto lingua franca of the world, Japaneseby and large can't speak English effectively. Yet few westerners ever learn Japanese tothe extent to conduct business transactions.

Japanese shoppers are also picky and conservative. Goods with a small scratch,dent, or blemish simply won't sell unless you cut the price way down, and few shoppers are willing to try something different. They think (and in many cases areRIGHT) that Japanese products are as good, if not better than foreign products. So why changebrands when you know you're satisifed with what you're using now? Plus, many US firms arestill ignorant of Japanese culture and buying behavior, and think whatever advertising worksin the US is good enough anywhere else.

Other problems are that foreigners expect the Japanese market to work the same as othernations, and it clearly doesn't. On the US-Japan trade deficit, more than 2/3 of it is in cars.But US car makers don't bother making special models that take into consideration Japaneseconsumer preferences, taxes on engine size, or Japan's cramped streets, so many models are too pricey or big. And when it comes to luxury cars the Japanese would rather drive a BMW or Mercedes. Some US and Europeancompanies have bought stock of struggling Japanese firms; how much this will change things is still yet to be seen.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. Consumer Apathy/IgnoranceOne other significant but often glossed over barrier is the nature of the Japanese themselves.This too is a problem which won't be going away overnight. While in the west people are taughtto think critically and analyse, Japanese are taught all the more to put up, shut up, and do whatthey're told. Thinking is again a group-oriented activity. In this group is a strong "villagementality", and anything outside the group is generally secondary, or worse, ignored. Charity andgrassroots movements are nearly unheard of in Japan. The ideas of personal growth, individualliberty, and privacy are not well defined in Japan. In fact, there is no real Japanese word for"privacy" at all, and the English word privacy has been borrowed (purabashi). Many Japanese infact mistakenly equate individualism with selfishness. Standing up foryourself is another new concept to Japanese. So whatever retailers charge, the Japanese justpay, no questions asked. A lot of Japanese media and TV also use sensationalism to sell, andobjective reality is often trampled over.What's that? Don't you pay $25 for a melon and $18 for a bottle ofaspirin?? Must be something wrong with your country's products -- there have been lots ofstories about shoddy or "dangerous" foreign goods...

And why are so many Japanese like docile sheep ready for the slaughter? Several reasons.One is the educational system, which is based on rote memorization. There is no critical thinkinginvolved -- only feeding back data. The goal is not real learning, it is only to pass the entranceexam for the next level up. Hence, Japanese memorize mile-long lists of English vocab and grammar, but are completely incapable of holding the simplest conversation. The same forevery other subject. Once you get into college, everything learnt is forgotten and the partybegins. Many students are so burned out after cramming every night for yearsthat they understandably have no interest in anything but getting some R&R,and have no knowledge or interest in anything else.Then they join a company and the whole grind begins all over again. Throughout, thegroup enforces rigid conformism. Individualism, genius, and creativity are squashed. The Systemis very good at mass producing obedient workers for Big Business.So what happens when you want change in government? Most people in other nations would vote for a reform candidatein the next election. Who's the reform candidate in Japanese elections? You'd never know. In manycountries, there's a debate, tv/radio discussion, etc. In Japan, elections consist of trucks thatrun around with speakers blaring, "Thank you! Thank you! Thank you! My name is Tanaka, thankyou! Thank you! Thank you!" Nothing concrete ever gets mentioned or promised by the candidates-- except buying votes through pork barrel projects, and nothing is demanded by the people.In fact, many people vote the way their companies tell them to -- whichever candidate willhelp out their business or grant more pork. Few politicians can do much of anything anyway sincethe bureaucrats can obsctuct whatever they want and are never voted out.

Worse yet is the bland, toilet-trained media, which when it comes to reporting politics gives"news" of, "The government stated today that blah blah blah", end of story. Some hour long newsshow 10 minutes of news, and 45 minutes of sports and weather. Just as in products, thereis the media information cartel called the "kisha", which is the press club. Do anythingdaring or report anything more than the National Party Line and you may findyourself frozen out of the Club and press conferences. Non-Japanese news sources have oftencaught the scoop on a scandal, since the Japanese don't do any deep probing and there are no lawsto protect whistleblowers from retaliation. Even so, more and more of theJapanese people are shopping abroad. Yet very few EVER wonder why Japan is so expensive.Most Japanese are completely apolitical and areligious anyway. The news is stodgy and littlemore than something that should be given to insomniacs who don't respond to strong drugs.So what do they do with their time? Usually drinking, smoking, karaoke, sports, and dashingmadly from one fad to the next. Here today, gone tomorrow. Out of sight, out of mind.

Conclusion, and Protecting YourselfTo end on a positive note, things are slowly improving in Japan. Continued pressure frommany nations as well as yet another year of the Japanese economy in Intensive Care is finallyresulting in some modest reforms and increased competition. Discounters are bypassing someredundant regional wholesalers, gasoline prices and rents are falling. Much more needs to bedone, but at last the ball is rolling.

So what can you do to avoid Consumer Rape? Several things. Don't keep your money in aJapanese bank -- you'll get neglible interest on it. Avoid big department stores -- you'll neverfind a bargain. Look for the discount stores near you--they are slowly increasing. Learn to cookyour favorite foods--it beats paying $30 at a restaurant. If you're large, bring as many clothesand shoes with you as you can. If you're a woman, bring lots of make-up. Look into mail ordersuch as The Foreign Buyer's Club, and cheaper stores like The Price Club, or Costco in Japan.See whatever movies and videos interest you before coming to Japan, since movies are veryexpensive here, as well as censored and delayed up to a full year. Some narrow streets inJapan have several vendors selling cheaper vegetables and fruits. Have yourfriends and family mail you vitamins, medicines, cosmetics, books and videos, instead of paying through your nose for such things in Japan. Sign up with a callback company for international phone calls or get ready to bend over and grab your ankles. There are lots of other ideas.Use your imagination a bit. Those that survive here are people who can MAKE DO WITH LES

. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Category: Negeri & Negara

|